Case 11: Getting bitten by not seeing it

This post is the 11th in my series looking at cases where it seems that "believing we are right" has led to bad outcomes, sometimes even spectacularly bad results, for leaders, teams and organizations.

For my upcoming book, Big Decisions: Why we make decisions that matter so poorly. How we can make them better, I have identified and categorized nearly 350 mental traps and errors that lead us into making bad decisions. The many high-profile situations that I have examined demonstrate the bad outcomes that can be produced by mental traps and errors. My premise is that, at the least, if we recognize and admit that we don't know the answer, we will put more effort into looking for better decision options and limiting the risks stemming from failure when making important decisions.

This case shows what can happen when mental traps and logic errors set up a leader to ignore mounting evidence countering common, long-held - and wrong - belief. The result was death and near derailment of a world-changing undertaking.

"BALDERDASH!"

Isthmian Canal Commission Chief Engineer John Walker believed when he took over the U.S. project to build the Panama Canal in 1904 that the theory that mosquitoes transmitted deadly Yellow Fever was "balderdash" and eliminating the mosquitoes was a waste of time, money, and manpower. Walker's belief rejected 50 years of evidence from medical research that the Aedes aegypti mosquito spread Yellow Fever. It ignored the "proof of concept" offered In 1901, when a yellow fever epidemic erupted in Havana: Dr. William Gorgas and his medical team eradicated the mosquito from Havana in eight months, halting the epidemic.

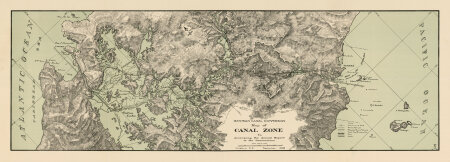

In November of 1904, cases of yellow fever began to appear in the Panama Canal Zone. Panic spread: 200 staff members resigned over a two-week span and three-quarters of all Americans left. Ultimately, 246 people came down with Yellow Fever and 84 people died. President Theodore Roosevelt,realized that Walker and other Canal Commission members were a major obstacle to Dr. Gorgas's planned attack on mosquitoes in the Canal Zone, so he forced their resignation. The new leaders he appointed gave medical officer Dr. Gorgas the resources he needed to end the epidemic and ultimately rid the the Canal Zone of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and the disease.

Why did Walker, a highly successful civil engineer who began his his career as Assistant Civil Engineer for the U.S. Engineering Corps, focusing on river and harbor work, and then became Chief Engineer and finally General Manager of the Illinois Central Railroad, reject the mounting scientific evidence that mosquitoes and not "bad air" spread the deadly disease?

He had been conditioned by long-made claims to believe Yellow Fever appeared in areas where "miasma" (bad air) and fomites (airborne particles) were prevalent. This was an Illusory Correlation (perceiving a relationship between variables when no such relationship exists).

His controlling personality led him into denying the evidence: He was a victim of the behavioral trap of Self Deception (when people deny or rationalize away the relevance, significance, or importance of opposing evidence and logical argument.to maintain a positive self image and the illusion of control over their lives).

When Walker dismissed the evidence of the mosquito theory of transmission he made the logic error of an Appeal to Ignorance (assuming a conclusion or fact based primarily on lack of evidence to the contrary, the error of which is described by the statement, “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence").

Walker's hard driving approach served him well when he was building railroads and ports. Yet, his charge to "get the canal built" encouraged his narrow "get 'er done" focus and amplified his desire to wave away all but the most apparent obstacles to success. What's important is often subtle and murky. When we are led to not look for what's less apparent, we can be led seriously astray.

I expect to publish my new book, Big Decisions: Why we make decisions that matter so poorly. How we can make them better, later this year. It will be an antidote for bad decision individual and organizational decision making. You can help me get it published and in the hands of decision makers whose decisions not only affect their lives but all of ours.

Learn more about Big Decisions: Why we make decisions that matter so poorly. How we can make them better and my special half-price pre-publication offer. Thank you!