Strategic Thinking & Strategic Action

Fostering strategic thinking and strategic action by organizational leaders since 2007.

Archive

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- July 2023

- August 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- July 2019

- April 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- October 2015

- March 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- April 2010

- October 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- May 2008

- February 2008

- August 2007

-

Action-oriented bias

- Nov 17, 2017 Trump trap: Action-oriented bias Nov 17, 2017

-

Approach-avoidance

- Sep 21, 2016 Approach or avoid? Sep 21, 2016

-

Bell curve bias

- Mar 28, 2020 We are biased by the bell curve Mar 28, 2020

-

Choice

- Oct 5, 2016 Managing choice Oct 5, 2016

-

Coaching

- Jan 7, 2025 Pick the best: Don’t let the bad drive out the good Jan 7, 2025

- Jan 22, 2024 Coaching and change Jan 22, 2024

- Apr 1, 2021 Let’s not be complacent about our ignorance! Apr 1, 2021

- Mar 10, 2021 So much can go wrong. Here’s how to make it go right. Mar 10, 2021

- Mar 10, 2021 Why settle? Go for the gold! Mar 10, 2021

- Mar 10, 2021 It's time for spring training. Are you ready to play on the A Team? Mar 10, 2021

-

Consensus

- Dec 6, 2016 No consensus for consensus Dec 6, 2016

-

Decision biases cases

- Oct 19, 2020 Short-sighted thinking: The case of the “hot new smartphone” Oct 19, 2020

- Sep 10, 2020 Changing our thinking to feel better. Yes, we do that! Sep 10, 2020

- Oct 24, 2019 Remember, history is written by the survivors Oct 24, 2019

- Oct 22, 2019 Beliefs about a group matter Oct 22, 2019

- Oct 15, 2019 Not knowing we don’t know Oct 15, 2019

- Sep 19, 2017 Case 12: Not missing the opportunity to lose billions Sep 19, 2017

- Aug 29, 2017 Case 11: Getting bitten by not seeing it Aug 29, 2017

- Aug 29, 2017 Case 10: When what worked didn’t work Aug 29, 2017

- Aug 28, 2017 Case 9: The climbers who perished by succeeding Aug 28, 2017

- Aug 28, 2017 Case 8: No accounting for incompetence Aug 28, 2017

- Aug 16, 2017 Case 7: Blind or incompetent? Perhaps both… Aug 16, 2017

- Aug 16, 2017 Case 6: Seeing what he wanted to see Aug 16, 2017

- Aug 13, 2017 Case 5: Getting burned by past successes Aug 13, 2017

- Aug 2, 2017 Case 4: I’m the boss, so I am right! Aug 2, 2017

- Aug 2, 2017 Case 3: The experts were wrong Aug 2, 2017

- Aug 2, 2017 Case 2: The battle that didn’t go as expected Aug 2, 2017

- Dec 12, 2016 Failure without facilitation: The French Canal Disaster Dec 12, 2016

- Oct 26, 2015 Decision traps, flaws and fallacies: Learn from my unexpected big decision Oct 26, 2015

-

Decision making

- Nov 6, 2024 Rise of the poker pros: 10 lessons for great success Nov 6, 2024

- Jan 5, 2024 What’s your magic number? Jan 5, 2024

- Oct 9, 2023 AI revisited: Will it ever make perfect decisions? Oct 9, 2023

- Sep 4, 2019 “The instant of decision is madness” Sep 4, 2019

- Apr 23, 2018 Despite our growing ignorance, we must decide Apr 23, 2018

- Apr 12, 2018 Can “Big Data” deliver “the right decision”? Apr 12, 2018

- Jan 18, 2018 The worst accident: “We’re going!” Jan 18, 2018

- Mar 8, 2015 10 surprising mental traps: Why we make bad decisions Mar 8, 2015

- Mar 10, 2014 Often wrong but never in doubt Mar 10, 2014

-

Decision making biases

- Mar 10, 2021 So much can go wrong. Here’s how to make it go right. Mar 10, 2021

-

Evidence

- Dec 16, 2016 Misuse of evidence can zap your strategy Dec 16, 2016

-

Evolution

- Aug 6, 2016 Smart phones on the savannah Aug 6, 2016

-

Gratitude

- Oct 25, 2017 Thank you for our connection Oct 25, 2017

-

Group decisions

- Nov 15, 2016 #2 error: Not using the group advantage Nov 15, 2016

- Oct 22, 2015 Open up your thinking: Make better decisions in a group process Oct 22, 2015

-

Leadership

- Nov 14, 2016 #1 error: The leader problem Nov 14, 2016

- Feb 1, 2016 Leaders who mislead: A tale of two movies Feb 1, 2016

-

Pre-mortem

- Sep 12, 2016 Thinking “as if” Sep 12, 2016

-

Risk

- Jun 9, 2020 The Black Swan and us Jun 9, 2020

- Jan 10, 2017 The risk of ignoring risk Jan 10, 2017

- Oct 14, 2016 Risk and regret Oct 14, 2016

-

Strategic planning

- Jan 4, 2025 California High Speed Rail to nowhere: Lessons for implementing our plans Jan 4, 2025

- Dec 17, 2024 Why New Year’s resolutions fail: The problem of implementation Dec 17, 2024

- Nov 10, 2024 Are you ready to bat? Nov 10, 2024

- Oct 9, 2024 Drift and big change challenge our success Oct 9, 2024

- Aug 19, 2024 Get real when you plan! Aug 19, 2024

- Apr 10, 2024 Bridge the strategy gap Apr 10, 2024

- Feb 23, 2024 Don't waste your time planning, unless... Feb 23, 2024

- Dec 18, 2023 The secret sauce of successful plan implementation Dec 18, 2023

- Nov 20, 2023 How to build commitment to change, revisited Nov 20, 2023

- Oct 3, 2023 Success Starts With a Big Vision Oct 3, 2023

- Aug 24, 2021 Sometimes you get what you need Aug 24, 2021

- Feb 25, 2021 Do you measure up? Feb 25, 2021

- Jul 28, 2020 Forget business as usual Jul 28, 2020

- Oct 9, 2014 What’s driving your organization? Oct 9, 2014

- Feb 20, 2014 This is not an infomercial Feb 20, 2014

- Feb 11, 2014 The Big Fail Feb 11, 2014

- Mar 12, 2013 Parsimony and planning Mar 12, 2013

-

Strategic thinking

- Feb 11, 2025 What to do when disaster ensues Feb 11, 2025

- Feb 27, 2024 Desirable difficulties Feb 27, 2024

- Jan 13, 2024 Business model question: Produce or provide? Jan 13, 2024

- Jan 5, 2024 What’s your magic number? Jan 5, 2024

- Jul 5, 2023 Think wide to succeed: How will you compete? Jul 5, 2023

- Mar 25, 2014 Flight 370 and strategic thinking Mar 25, 2014

-

Strategy

- Mar 17, 2025 Are you getting your share? Mar 17, 2025

- Feb 24, 2025 Know who you are up against! Feb 24, 2025

- Jan 18, 2025 Be better than the competition Jan 18, 2025

- Jul 23, 2024 Your pricing says it all… But what does it say? Jul 23, 2024

- Jun 23, 2024 We are people, not transactions Jun 23, 2024

- May 22, 2024 Is excellence - or failure - ahead? Answer five questions to know May 22, 2024

- Apr 8, 2024 What do your customers expect? Apr 8, 2024

- Nov 13, 2023 Demand a great brand! Nov 13, 2023

- Oct 31, 2017 Why not plan to be great, like Elon Musk? Oct 31, 2017

-

Success

- Jul 24, 2019 22 principles I have learned from being an athlete Jul 24, 2019

-

Sunk cost fallacy

- Mar 21, 2015 Sunk cost fallacy: Throwing good money after bad Mar 21, 2015

Short-sighted thinking: The case of the “hot new smartphone”

Here’s a story that shows what can happen when we don’t look beyond the expected and familiar, what relates to us, and what confirms our thoughts.

Changing our thinking to feel better. Yes, we do that!

In the 1980s, I had encounters with two bank CEOs whom power and money biased to make very bad decisions that hurt themselves, their employees, customers and the U.S. economy. Both later tangled with the law for their misdeeds.

With that background, you will understand why I am astonished about a much more recent and much larger case of banking misconduct, for which I believe no one has yet to serve time in custody. This case amplifies the decision-making errors I saw in the lead-up to the savings and loan crisis.

In February 2020, Wells Fargo, the nation’s fourth largest commercial bank, stunningly admitted that it had assessed customers millions of dollars in fees as employees falsified records, forged signatures and misused customers’ personal information to open fake accounts to meet unrealistic sales goals. The bank said its leaders knew of the misbehavior, including “violations of federal criminal law,” as early as 2002 but did not stop it until 2016.

Remember, history is written by the survivors

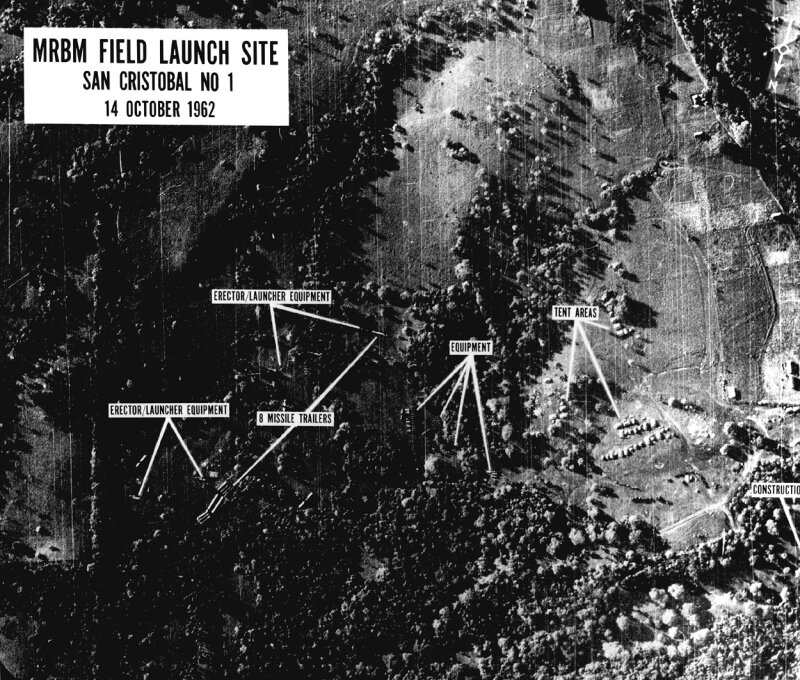

We are urged to learn from history. But what if the history is biased? Here’s a case showing how slanted history can lead to bad decisions. In the Cuban Missile Crisis, U.S. advisors were mislead by the fallacy of silent evidence, that is, not seeing the full story when looking at history, just seeing the rosier parts of the process reported by the “winners.” U.S. policy was tragically misguided because of survivorship bias, that is, concentrating on and giving undue credit to the people, things or interpretations that "survived" the process and inadvertently overlooking those that didn't because of their invisibility.

Beliefs about a group matter

Here’s a story about what can go wrong when we hold beliefs about a group and attribute these beliefs to the members of the group. The Battle of Little Bighorn, also called Custer's Last Stand, took place in Montana Territory on June 25-26, 1876, between the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes and the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the U.S. Army. The Battle of the Little Bighorn was a stunning victory for the Native Americans. The 7th Cavalry, casualties numbered 268 dead, including Custer, and 55 wounded. How Custer viewed the Indians opposing him led him astray.

Not knowing we don’t know

To lack relevant knowledge without realizing it can have disastrous consequences. Consider, for example, the underestimation of the risk of a nuclear accident when constructing the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant power plant in Japan. The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant disaster offers a stark example of what can go wrong when we rely on a small and biased sample of data.

Case 12: Not missing the opportunity to lose billions

Bernie Madoff's investors believed that his fund was rock-solid. He promised consistent annual returns of 10% to 12% and seemingly delivered on this promise for years. HIs Ponzi scheme has cost more than 40,000 investors who believed in him $6 billion in principal, even after recovery of $11.5 billion in investor's funds. Ponzi schemes like Madoff's succeed for longer or shorter periods because they play on greed. "Wanting in" and our desire to "get the payoff" can lead us to suspend disbelief and place trust where, indeed, it is misplaced.

Case 11: Getting bitten by not seeing it

Isthmian Canal Commission Chief Engineer John Walker believed when he took over the U.S. project to build the Panama Canal in 1904 that the theory that mosquitoes transmitted deadly Yellow Fever was "balderdash" and eliminating the mosquitoes was a waste of time, money, and manpower. Walker's belief rejected 50 years of evidence from medical research that the Aedes aegypti mosquito spread Yellow Fever. His charge to "get the canal built" encouraged his narrow "get 'er done" focus and amplified his desire to wave away all but the most apparent obstacles to success. What's important is often subtle and murky. When we are led to not look for what's less apparent, we can be led seriously astray.

Case 10: When what worked didn’t work

Yahoo CEO and former Google executive Marissa Mayer believed that she could turn around Yahoo when many others before her could not. Whether turning around Yahoo was possible cannot be known. But what does seem evident is that mental traps made the task even more difficult for Mayer. Her story shows us just how extraordinarily difficult it is for us to "unlearn" what has made us successful when new circumstances demand a different approach.

Case 9: The climbers who perished by succeeding

Mountain climbing guide Rob Hall believed that his expedition plan would get Mount Everest climbers in his charge onto and down from the summit. Yet, many climbers found themselves descending in darkness, well past midnight, as a ferocious blizzard enveloped the mountain. Five people died in this highly publicized 1996 disaster and many others barely escaped with their lives. Hall's party encountered the worst of outcomes because options were not recognized and the judgment of others besides Hall went unheard.

Case 8: No accounting for incompetence

PricewaterhouseCoopers' partner and accountant Brian Cullinan believed that he and his associate were well prepared to properly dole out the envelopes with winners' names to presenters at the 2017 Oscars ceremony. Cullinan made the biggest Oscar award mistake ever by handing presenter Warren Beatty the wrong envelope. Beatty's on-stage partner, Faye Dunaway, announced “La La Land” was the winner when “Moonlight” was actually the best picture winner. The accounting firm partner was likely entrapped by many mental errors and biases. Working for a big-name firm and having a big title does not protect one from biases and traps. Indeed, it can lead to overlooking evidence and both rash action and stultifying inaction.

Case 7: Blind or incompetent? Perhaps both…

Lehman Brothers CEO Richard Fuld believed that the investment bank was adequately capitalized when it increased its leverage from 12-1 to 40-to-1, became a major player in securitizing subprime mortgages, relied on risky credit default swaps for protection and engaged in accounting maneuvers that disguised how much debt the firm had taken on. Also, he believed that the U.S. government would bail out the firm when the policies and actions he had enabled put the firm on the brink of failure in 2008. Contrary to Fuld's belief, Lehman Brothers was woefully undercapitalized as the financial crisis arose. The federal government walked away from an implicit "too big to fail" tag that Fuld and others thought would be applied to the firm. Lehman Brothers failed and Fuld was disgraced. Three big mental traps jump out of Fuld's folly.

Case 6: Seeing what he wanted to see

Galileo stubbornly believed that Saturn was three planets in close orbit. This belief, which the Italian astronomer clung to until he died, belied what otherwise was his use of the scientific method: Other astronomers with stronger telescopes reported that what he saw as multiple planets was instead one planet with previously unknown rings around it.. Multiple mental traps and errors may have clouded Galileo's vision.

Case 5: Getting burned by past successes

Samsung's leaders believed that the smartphone giant had a winner when it introduced its flagship Galaxy Note 7 smartphone with a new longer life lithium-ion battery. After weeks of reports of phones bursting into fire, Samsung issued two separate recalls and ultimately had to permanently withdraw the phone from the market. Here are the mental traps and errors that likely misled Samsung's leaders.

Case 4: I’m the boss, so I am right!

Uber Technologies CEO Travis Kalanick believed that through confrontation he could make the firm supreme and dictate the rules for ridesharing and driverless cars. His approach led to a boycott and great reputational damage for the company and for him personally. Kalanick seems to be a "poster child" illustrating the ill effects of biases and traps.

Case 3: The experts were wrong

Hillary Clinton's campaign team believed that with Donald Trump as her opponent she would be elected President. Winning the popular vote did not produce the victory that her team predicted: Clinton lost in the Electoral College. Here are some mental traps and fallacies that likely led the Clinton team to err and predict victory.

Case 2: The battle that didn’t go as expected

Confederate General Robert E. Lee believed that his troops could overrun the Federal's front line at the battle of Gettysburg. He was wrong: Pickett's charge by 15,000 Confederate soldiers against 6,500 entrenched Federals resulted in over 6,000 Confederate casualties and ended Lee’s last invasion of the north. Here are several traps and errors that may have led Lee to believe the charge would succeed.

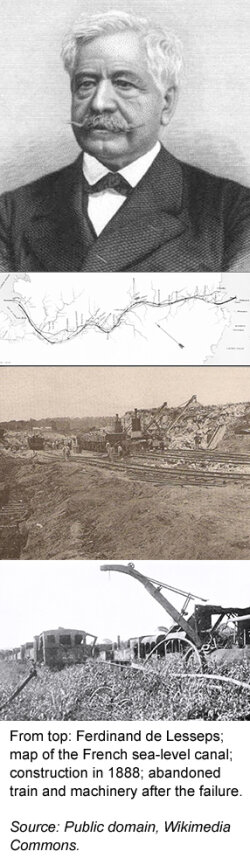

Failure without facilitation: The French Canal Disaster

In 1879, the Congrès International d'Etudes du Canal Interocéanique (International Congress for Study of an Interoceanic Canal) was convened in Paris under the auspices of the Société de Géographie de Paris to consider proposals to build a canal across Central America, from the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean. Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French ex-diplomat who had spawned and led the company that created the Suez Canal, chaired the conference and dominated the discussions and the decision making. Despite an immense amount of evidence against the success of a sea-level canal across the Isthmus of Panama, de Lesseps' vision prevailed. More than 22,000 lives were lost and thousands of investors were out the equivalent of nearly $6 billion in current dollars when that Panama canal venture finally collapsed in 1889. Why was it that the errant views of one Frenchman won out over the combined wisdom of the engineering community, the financial community and many others who had spent time scouting the terrain and who had identified the huge problems of disease, torrential rain, dense rain forest, raging rivers and mountains that stood in the way of success? Why in this striking case did not the underlying wisdom of the group prevail?

Decision traps, flaws and fallacies: Learn from my unexpected big decision

My life was changed by unexpected input into my decision making from a noted journalist and World War II veteran whose plane was shot down and who then spent two years in a German prisoner-of-war camp. I pursued my MBA and a career path which has led to meaningful business roles, strategy consulting and, I hope, useful thought leadership. Making good decisions is at the heart of effective strategic planning and strategic management. That's why I have been taking a deep dive into how we can make big decisions better. Let's examine my life changing exchange with Emmett Dedmon to see what might have been at work that affected my decision making process.